From the agitation in Gujarat after gau-rakshaks (literally, cow protectors) attacked Dalits to countrywide protests after the suicide of Rohith Vemula in Hyderabad Central University, Dalit politics is on the boil. The fact that India’s biggest state Uttar Pradesh goes to polls next year has increased stakes for all political parties. The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), which primarily relies on Dalit votes, is a major force in the state.

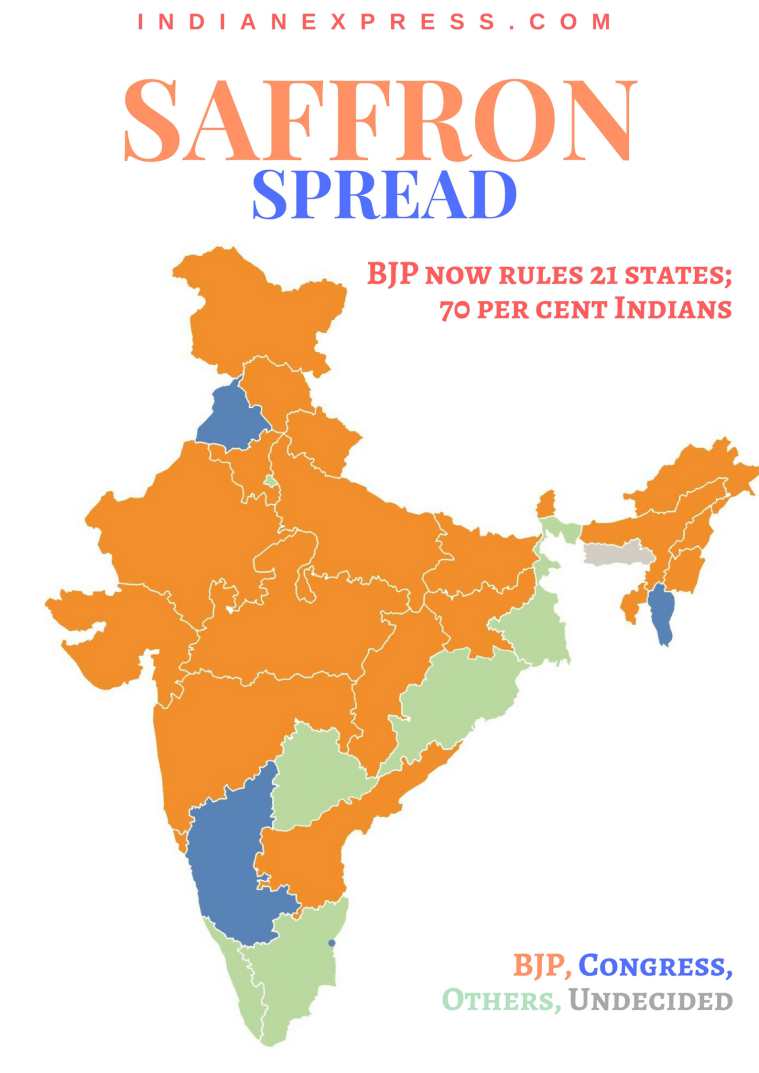

In the 2014 parliamentary elections, the BSP did not win even one seat despite getting close to 20% of the votes polled. Experts attribute this to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) successful dent in the Dalit vote, aided by communal polarization in west Uttar Pradesh.

There is no reason why the BJP, which won 71 of the 80 seats in the state then, would not want this to continue. Its opponents, including the BSP’s Mayawati, are using every incident of atrocity against Dalits to portray the BJP as an anti-Dalit political force.

But there is more to the angst among and against Dalits than just this.

Sanjay Paswan, a former minister and senior Dalit leader from the BJP, wrote in The Indian Express last week of the “need is to depoliticise the Dalit discourse and strive towards an independent, objective, dispassionate and solution-centric Dalit narrative”.

Efforts to promote Dalit capitalism through bodies such as Dalit Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry could be one solution. Can these help annihilate caste-based exploitation in India?

Consider crimes against Dalits. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data shows that crimes against Dalits increased from less than 50 (for every million people) in the last decade to 223 in 2015. Among states, Rajasthan has the worst record although Bihar is a regular in the top 5 states by crimes against Dalits. Gujarat had a rate lower than all-India average (for crimes against Dalits) in 2011. It has crossed the mark since then.

Many social scientists have questioned the belief that economic advancement of Dalits can reduce crimes against them. In a recent article in The Indian Express, political scientist Pratap Bhanu Mehta says that far from being a solution, this could be a trigger for more crimes against Dalits. “Economic advancement alone will not diminish the psychic traumas of caste; it may actually create more conflict… The empowerment of these groups rather than becoming a celebration of justice becomes a sign of fatal concoction of guilt and loss of power...”. S.S. Jodhka, a professor of sociology at Jawaharlal Nehru University had also echoed similar views in a 2015 Mint article which looked at increasing violence against Dalits.

To understand that whether the economic advancement of Dalits has indeed caused a spike in crimes against them, Mint looked at differences in asset ownership: between all households and scheduled caste ones that own certain assets (TV, computer/laptop, telephone/mobile phone and scooter/car); and between all households and scheduled caste ones that do not own certain assets (TV, computer/laptop, telephone/mobile phone, scooter/car, radio and bicycle).

Expectedly, the numbers are positive for the first category and negative for all states except two—Gujarat and Assam—in the second category. This shows that average asset ownership is lower among Dalits in most parts of India.

Interestingly, the inequality between Dalits and others is lower than the national average in Rajasthan, the state with the highest proportion of crimes against Dalits.

Punjab, which sees the highest inequality between Dalits and others, has fewer crimes against Dalits.

Indeed, several states conform to this inverse relationship although there are outliers such as Assam, where Dalit households are actually better off than all households in terms of asset ownership, but which also sees among the least number of crimes against Dalits.

Sure, such simplistic comparisons are far from definitive, but they buttress the argument made by Mehta and Jodhka.

If better economic means is to promote the status of Dalits in the society, then it should also reflect in increasing political representation. The constitution provides for mandatory reservation of seats for Dalits and tribals in the Lok Sabha and state assemblies.

However, the representation of Dalits above this mandated quota is abysmal. Data collected by the Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University shows that in 63 state assembly elections held since 2004, scheduled-caste candidates found it extremely difficult to get elected from a unreserved seat. In 44 elections, they lost. Often Dalits are not given tickets by major political parties from unreserved seats.

Neither Uttar Pradesh, the state where the BSP is a force, nor the BJP-ruled states have a good track record. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) ruled Tripura stands out as an exception with a 5% share of scheduled caste candidates being elected from unreserved seats.

It can’t be denied that economic development and affirmative action have helped improve the lot of Dalits, eve n though the advance is far from satisfactory. Still, even this limited advance has faced hostility and meant no increase in political representation.

Maybe that explains the crimes against Dalits and also the Dalit anger spilling onto the streets.